‘There is something unnerving about people who can’t be located dead or alive. They upset our sense of space – surely the missing ones have to be somewhere, but where?’

– Margaret Atwood.

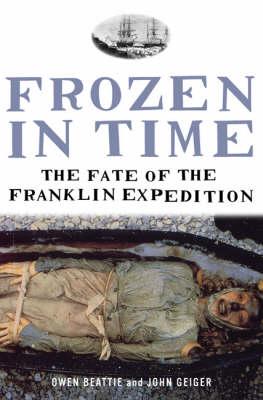

Whenever I visit the library, I make a beeline for the travel section, and crouch down to inspect the lowest shelf, where I can be sure to find a handful books about polar exploration. Fortunately, there must be another soul in the district who is just as fascinated by the poles – and the people who traverse them – as I am, as there is regularly a ‘new’ book or two gracing the shelf. In this case, it was ‘Frozen In Time,’ a book about the fated Franklin Expedition. I snapped it up. I couldn’t resist. The cover, for a start, was one of the most poignant I’ve ever seen, and I don’t give kudos to book covers for nothing. In terms of impact, this was like a punch in the face. John Torrington is the man on the cover of this particular edition. Torrington died on the 1st of January 1846. I’ll let that sink in while you take another look at his extraordinary preservation.

Margaret Atwood wrote an absorbing, yet suitably unsettling introduction to the book.

‘In the fall of 1984, a mesmerizing photograph grabbed attention in newspapers around the world. It showed a young man who looked neither fully dead nor entirely alive. He was dressed in archaic clothing and was surrounded by a casing of ice. The whites of his half-open eyes were tea coloured. His forehead was dark blue.’

‘…Here is someone who had defied the general ashes-to-ashes, dust-to-dust rule, and who has remained recognisable as an individual human being long after most have turned to bone and earth.’

‘The man in the sensational photograph was John Torrington, one of the first three to die during the doomed Franklin expedition of 1845. The stated goal of the expedition was to discover the Northwest Passage to the Orient and claim it for Britain.’

In 1981, an archaeological team from the University of Alberta scoured the south coast of King William Island ‘one of the most desolate places in the world’ searching for human remains. They wanted to discover clues that could hopefully lead them to an understanding of the last days of the Franklin Expedition’s 129 men, as it was here, in 1848, where the expedition came to a cold, miserable end.

On the second day of their search, they found bones. ‘Most of the remains were found exposed on the surface…The texture of the bones illustrated the severity of the northern climate. Exposed portions were bleached white and powdery flakes of the outer bone surface cracked and fell off if handled too roughly. Sharing the exposed surfaces were small and brightly coloured colonies of mosses and lichens, anchored firmly on the sterile white of the bone as if braced for another harsh winter.’

The bones showed evidence of debilitating scurvy, a disease which effected European expansion and exploration expeditions starting from the 16th Century. Symptoms included ‘ulcers, rictus of the limbs, spontaneous haemorrhages in almost all parts of the body – and a bloom of gum tissue that enveloped what teeth had not already fallen out, producing a terrible odour.’ It was only in 1917 when the root cause of scurvy was discovered.

The finding of bones incited three further expeditions over the following five years. Each investigation uncovered new leads, and the eventual exhumation of three of Franklin’s men; John Torrington, John Hartnell and William Braine, which is where the emotions start to stir more frantically.

‘On 12th of August 1984, having erected a tent shell over the grave to protect it from the elements, the University of Alberta researchers began to dig through the ground of Torrington’s grave…Soon after the uppermost levels of the permafrost had been chipped, broken and shovelled away, a strange smell was detected in the otherwise crisp, clean air.’

I most certainly started to toy with the idea of my own mortality, and what will happen to my body when I go. I can’t even begin to imagine how researchers really must have felt on uncovering these preserved young men. (I say young, and they were, early twenties to mid-thirties.)

‘The first part of Torrington to come into view was the front of his shirt, complete with mother-of-pearl buttons. Soon, his perfectly preserved toes gradually pocked through the receding ice…But for artists’ portraits and a few primitive photographs, who living today has ever seen the face of a person from the earlier part of the Victorian era, a person who took part in one of history’s major expeditions of discovery?’

Following the painstaking excavations of the three men, samples of tissue, hair and bone were analyzed, to validate or defeat Owen Beattie’s theory about the catastrophic impact that lead poisoning had on Franklin Expedition. Preservation of food through canning was still a fairly new innovation, and it transpired that some of tins uncovered by researchers, were flawed.

‘…lead played an important role in the declining health of the entire crews of the Erebus and Terror – not only in their loss of physical energy but increasingly in their minds’ despair. Loss of appetite, fatigue, weakness and colic are some of the physical symptoms of lead poisoning. It can also cause disturbances of the central and peripheral nervous system, producing neurotic and erratic behaviour and paralysis of the limbs.’

Torrington, Hartnell and Braine were all victims of tuberculosis and pneumonia. But it was the lead entering their bodies, during the early stages of the expedition, which weakened them enough that they were susceptible to the illnesses which eventually killed them off.

As to the question why did the Franklin expedition fail so spectacularly – there is no single answer. What this astonishingly well researched book does is bring together the multiple threads, and provides as good an explanation as I expect we’re ever going to have.

This revised edition of ‘Frozen In Time’ was published by Bloomsbury in 2004.