This will be the last post I publish on Wyrd Words & Effigies*. I can’t think of a better way of bringing this lengthy journey (I’ve been publishing here since 2013) to a close than by featuring a conversation with one of the most significant figures to have played a role in my life as a writer.

I was eighteen (I’m thirty-six now) when I met renowned Teesside poet Bob Beagrie and ever since, he’s been instrumental in my growth as a wordsmith. When depression has made writing impossible – and it’s happened many times in the years we’ve known each other – Bob was always one of those letting me know I wasn’t done yet, that my words would come back home.

As an anxious, anorexic, introverted writer, being introduced to the Teesside Literary Scene by one of its most influential and prolific figures changed my life. I was inundated with opportunities to develop and hone my craft, and what had been a solitary, confined existence began to open up. For the first time, I was surrounded by people who got me, and I flourished. My life’s work – writing about the most northerly reaches of our planet – was arrived upon mostly thanks to Bob being in tune with what made my heart howl and influencing me to explore the reaches of its echo. I’m incredibly proud to have been mentored by Bob and to call him my friend, and it’s with great pride I present our conversation today.

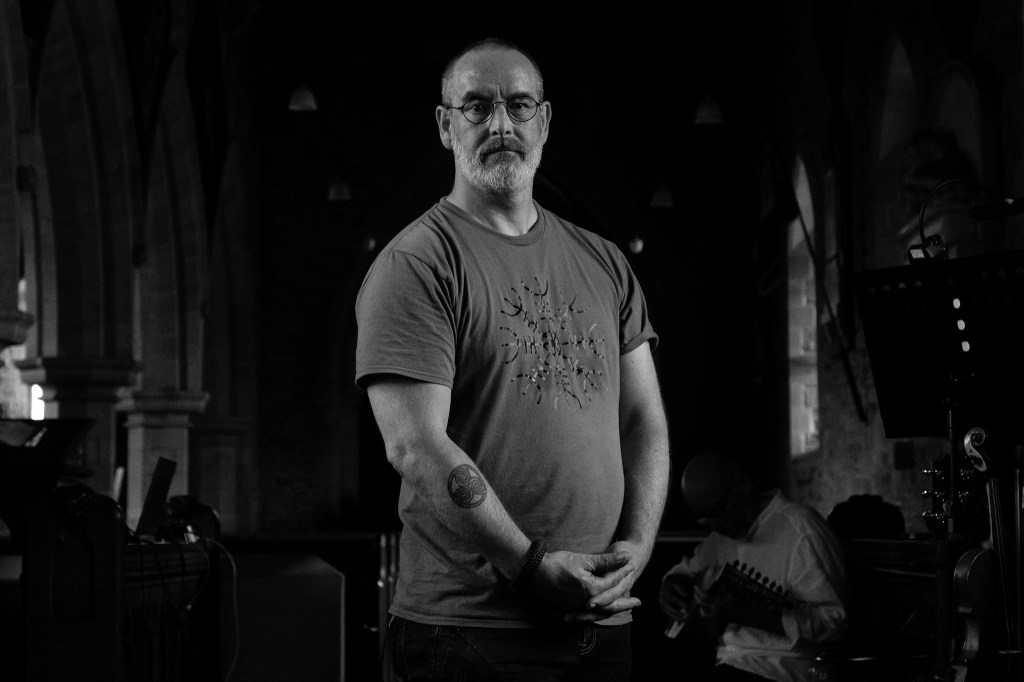

Bob Beagrie is an award-winning poet and the author of twelve books and six pamphlets. His work has been translated into Finnish, Estonian, Gaelic, Danish, Urdu, Spanish, Karelian, and Swedish. Bob is also a playwright, the co-director of Ek Zuban Press and Literature Development, a senior lecturer in creative writing at Teesside University and one-half of the experimental music and spoken word collaboration Project Lono. His latest book, The Last Almanac (Yaffle Press), is a remarkable roam of poems penned over twenty years, demonstrating Bob’s incredible breadth of poetic prowess.

For those readers in the North East of England, on Friday the 23rd June, Bob will be hosting Poetry and Song from the Firepit: A Midsummer Celebration in Middlesbrough featuring poems, live music and songs from Teesside’s troubadours, players and songsmiths.

*I’ll be establishing a new blog and will share a link when it’s live.*

Welcome, Bob! Whereabouts are you writing to us from, and how is your day shaping up?

Hi Katie, I’m writing from my spare room, which used to be my daughter’s bedroom when she lived here. My day is shaping up well, I think. I am due to do a session on performance skills this afternoon in a primary school, preparing the children for the launch of their book based on their visits to RSPB Saltholme, so I’m looking forward to that. It will be a lot of fun.

I recently finished reading your newly published poetry collection, The Last Almamac, which was luminescent. I want to rave from the rooftops about the poetic magick of it all! How was the journey from plan to publication and how are you feeling now it’s out in the world?

Thank you, I am so pleased that you like it. The book is composed of poems I’ve written over twenty years or so, but which never fit into a planned collection although lots have been published in magazines, journals and anthologies. I had a look at them all and decided that there was an underlying theme of connection / disconnection with nature, the environment and seasonal change. So, with that in mind I began experimenting with different arrangements and finally decided to order them as a kind of calendar of days running through the year, which kind of worked even though it is twenty years compressed into one.

Now that it is out in the world, I hope people enjoy it and connect with it. It’s very different to my other collections and so it might surprise a few people.

Was the title The Last Almanac in your head when you initially had the idea for the book or did it come later in the creative process?

The collection was originally titled ‘Everything Under the Sun’ but once I had arranged them into a calendar of days, I saw it as an almanac. Because there is a concern in quite a few of the poems around climate change and the threat we pose to nature and ourselves I thought The Last Almanac had a good ring to it, perhaps prophetic. However, because the book contains so much of my life it could also be read as ‘my’ last almanac which reflects the sense of mortality which also runs through many of the poems.

The book itself is gorgeously produced. How has your experience been working with your publisher Yaffle? Is this the first time you’ve collaborated?

Yes, this is the first time I have worked with Yaffle and I agree, their production values are great. The book is very beautiful and it’s the first I’ve published that has French folds. The editing process, working with Michael Farren was a careful and painstaking experience. He has a sharp eye and raised lots of questions which made me reconsider aspects of many of the poems, justify my creative choices and rework parts so they fit together more coherently as a whole. Having an editor you can have in-depth discussions with about seemingly minor points is a fascinating process and really encourages you to tighten up the work.

If it was feasible, I’d ask you to describe the creative process behind every poem in the book, but I’ll settle for one! What’s the story behind the creation of Film Poem?

Ah, Film Poem, well that is a very odd poem, haha. It is a very dream-like, mythic, fairytale, folk horror kind of thing. It is partially based on the story of Peter and the Wolf which Sergei Prokofiev wrote for the musical composition in 1936. Some of the lines are straight adaptations from it, such as “What kind of bird are you if you can’t fly?” and “What kind of bird are you if you can’t swim?” and there is an array of animals mentioned, the wolf, the cat, the duck, the wasps etc, and I had a vision of a boy and an old man essentially being the same person but becoming aware of one another’s ghostly presence in the same location, and there being an element of suppressed trauma, perhaps a collective atrocity which made me think of the hanging of the old woman as a witch, and how such collective acts of violence become the basis for ritualised behaviour, so ‘they are wearing wolf-masks at the fair’ might be part of a sacrificial ceremony of sorts, like in a carnival.

So, all these fragmentary elements came together to create the content. However, I was also interested in experimenting with parallelism, as I’d been reading about the semantic and syntactic parallelism within classical Chinese poetry from the Tang period, and also the aesthetics of fragmentation within Rilke, Eliot and Anselm Hollo. So that provided a possible approach for the composition, which I wanted to keep a link to musical aspects of the original inspiration, so that lines and images are threaded through and resurface like an orchestral piece. I’m not sure if it really works but it was an interesting experiment and it produced something that is quite odd, unsettling and uncanny.

Can you talk through your typical process of writing a poem?

A poem, for me, usually starts as an odd feeling at the back of my head, around the base of my skull, and its quite a distracting thing, a nagging and I can become quite irritable with day to day things. I usually need some time alone then, to go into it and feel my way into the mindset, trying to open up to it. I think this is what Keats was on about when he coined the term ‘negative capability’. Then I find myself scribbling phrases and descriptive images onto bits of paper without thinking of any order or arrangement or any meaning really, just trying to tap into that feeling. In the process of that certain phrases link up through a kind of magnetic attraction or repulsion and it kind of organically grows from there, until I start to see a shape or theme or coherence to it all.

The next stage is finding the shape of the material which I sometimes take through various possible forms. Sometimes I use a closed form like a sonnet or a villanelle or a pantoum or whatever, just as a way of distilling the material and finding what its really about. Sometimes I’ll stick to the closed form’s rules and other times I feel the poem is being restricted by the form and wants to go somewhere else so work the revised material through a more intuitive patterning. This is how, I interpret, Denise Levertov’s organic composition, if that all makes sense.

Why and when did you start writing, and who did you have encouraging you in those fledgling years?

I wrote stories as a child and teenager but didn’t really have any exposure to poetry until I started my degree in Creative Arts, so looking at the work of the Beats and ee cummings and the Black Mountain Poets was a complete revelation to me, I remember thinking, “Wow, I didn’t know poetry could be like this!”

But I started taking my writing (short stories) more seriously when I went to Trev Teasdel’s writing workshop at Berwick Hills Library back in 1986 or 1987, and he encouraged me to get involved in the local writing scene, The Writearound Festival, Outlet magazine, Teesside Writers Workshop, all of which was exciting and very nurturing. Trev also encouraged me to apply to do a creative writing degree which I’d never have had the confidence to do without that support.

I first learned the name Bob Beagrie when I was in college. My English teacher told me about KENAZ, the cutting-edge creative writing magazine you were publishing through Ek Zuban Press. How was it to be one of those at the helm of this extraordinary publication? Could you have predicted the massive impact it would go on to have on the literary scene in Teesside?

That is really nice to hear. It was very exciting and there was a dynamic energy around KENAZ and the live events we were putting on at the time, mixing poetry (visiting big names and local poets / spoken word artists) with bands and musicians and dance in an experimental way, and stressing a participatory nature of community involvement and collective ownership of our own arts / literature scene.

I remember several times standing watching a particular act or set of acts at say KENAZ Live or The Electric Kool-Aid Cabaret and thinking this is as good an event as anywhere in the world, totally class, and it’s happening in Boro, and it won’t even be acknowledged in the wider literature world because Teesside is largely invisible on the UKs cultural map. But maybe it was that which gave it its real edge.

On the subject of Ek Zuban, what was your experience of running a publishing house like? (I did it for a short while. It was one of the most stressful things I’ve ever done!)

Yes it is very stressful. I couldn’t do it alone. There is too much to attend to but working together with Andy Willoughby we (largely) complemented one another’s skill set so it lessoned the workload and stress. It was very exciting to be publishing local writers within the context of international literature due to the connections we built with writers from Holland, France, Denmark, Estonia, and Finland. Looking back, that internationalism was such an important thing, especially when you consider the xenophobia and anti-European sentiment that was being stoked on mainstream media at the time.

When I first became aware of a roaring literary scene in Teesside, you and fellow creative writing lecturer and poet Andy Willoughby were always at the forefront of almost everything. Hearing your name without Andy’s was rare, and vice versa. How did you two meet, and what’s the secret behind your long-lasting friendship and working relationship?

Yes we worked very closely together for around 16, maybe 18 years, doing Ek Zuban as a press, series of live events, projects and workshops. I remember going into a shop once and this boy of around 11 years old saw me and said to his mam, “Look, its Bob and Andy” even though I was on my own, haha.

I met Andy briefly before I went to do my degree and before he went off to Japan, at a Writearound event I think, but we each thought the other was an asshole. Then years later when I was working as the Literature Officer at Cleveland Arts Andy and running The Verb Garden, Andy came to some of the events, then got in touch with me to talk about setting up The Hydrogen Jukebox events in Darlington with Jo Colley, and I helped out a little and supported it. Then we did a few little projects together and things began to grow and we applied for some funding to do The Flesh of The Bear Anglo-Finn Poetry Exchange and got an Arts Council grant to develop it. From there we set up Ek Zuban and started to think big in terms of local and international impact. If Teesside was invisible in the eyes of the UKs literary culture then we thought, fuck it, we’ll do things on a pan-European scale.

We don’t work together now, I think that kind of intensity often burns out and implodes, and in 2019 we decided to go our separate ways professionally, but we are still good friends.

Teesside has been viewed with unkind eyes by many writers. (I have to admit your work has, over the years, helped me warm to what was home from the age of fifteen.) The novelist Sheila Kay-Smith said the area was ‘a landscape of fire and horror, a frontier-stretch of hell.’ It may seem an idiotic question, but how does it make you feel, as someone so profoundly inspired by this place, to read lines like this?

I think she is right, or at least was right when we had a steel industry and I do love old post-industrial wastelands, infused with that sense of hauntology and abandonment. I have a complex relationship to Teesside, love it and hate it and often despair over it, which is probably why I write about it so much. Now the steel industry has gone we have a bit of an identity crisis, and need a new narrative. I think that’s where writers and artists come in, to help shape the stories of who we are in a changing world.

From your perspective, what is it like to be a writer living and creating in Teesside in 2023?

Like I said, it often feels invisible and as a result I often feel invisible. However, at times that has been what has given me the licence and freedom to write something new, ambitious and even crazy, like Leasungspell.

We are similar in that not writing makes us fret. What do you need to accomplish in a day, writing-wise, so you don’t find yourself in that uncomfortable state of mind?

It’s not really possible for me to write every day but if I don’t give myself time to write after a few days I do start getting fretful, distracted and irritable. As I’ve got older I have paid more attention to this ebb and flow of creativity and if it’s there I have to jump on it and give it the time it demands before it washes away. During these periods I get obsessive and consumed by the process, but if it’s not there I have learned not to worry about it. I trust that it will come back, so I might paint do tai chi or kung fu or something else with my energy.

Do you have a favourite place to write?

No, not really, I write anywhere and anywhen and often on anything, envelopes, scraps of paper etc, whatever is at hand.

Watching you perform poetry on stage is a very ritualistic experience for me. I’ve always left your performances feeling more alive than I’d felt going in. The uniqueness of your delivery is quite unlike anything else I’ve ever witnessed. What would you say has helped the most in your development as a performer?

Thank you, Katie, that is a lovely complement. I think it comes from originally from the degree in creative arts I did at Crewe & Alsager College, because it was focused on integrated arts which meant collaborating with actors, dancers, visual artists, musicians to create cross disciplinary performance work, some of which was very experimental and avant garde, which was a shock to me when I first joined the course because I was a shy writer who had never really performed before, but it gave a the tools to adopt different personae who could step in and do it for me. Since then, I’ve worked with loads of talented musicians which has taught me about timing, pace, presence, projection, tempo etc, and I also think that doing martial arts (kung fu and tai chi, which I’ve done for nearly 30 years now) has helped me to explore the physicality of performance.

Do you let anyone listen to or read your works in progress?

Yes, I think sharing work-in-progress is a vital part of the editing and shaping process. I have often read poems out live at events as a way of testing out the rhythms and cadences and then done some revision and serious restructuring.

I’ve had enormous struggles with social media though I’m working on not taking it so seriously these days. How you handle being active online and what you consider the pros and cons of life on the internet?

On the whole I find it extremely useful to build connections that would have been impossible to do pre-internet days. Its useful for advertising events and publications, obviously. But I do see so much toxic stuff on there too. Its easy to get drawn into that, and I think everyone has some experience of that and it can turn bitter and aggressive very quickly. However, if I think of it like, ok, I’m in a busy pub and someone is kicking off at a table close by, I don’t have to join in, I don’t know what’s caused it and really its none of my business as long as its not turning violent, so I can be aware of it but there is no need to get involved and if it starts getting out of hand I can leave. What does piss me off is the way some people feel they can talk you on social media with an attitude they would not dare adopt in a face to face situation.

Do you have a favourite poetic form to write in?

I do love sonnets and I’ve written lots of them, or at least pseudo-sonnets. I find the structure is quite magical in the way it develops an idea, focuses upon concrete images that work as synecdoches, then flips it all around in such a limited field. Don Paterson’s anthology ‘101 Sonnets’ is a must read for any serious poet. His introduction to the form is mind-blowing.

You’ve lived most of your life in Middlesbrough. Still, your profound connection to the natural world is unmissable. You’re absolutely in tune with the ways of the wild, and this is a beautiful, humbling thing to witness through your work. In as few or as many words as you wish, could you talk about the kinship you feel with wild things and how this influences your writing?

Growing up in Middlesbrough and being rooted in the urban landscape is also a key theme in lots of my work, but you are right, nature and the connection with it is a very important feature within lots of my poems. We are lucky to have such beautiful countryside just a few miles out of town and green corridors running through it. This was so important for me during lockdown, and I’d go out on my bike and explore the tracks and paths between estates, retail parks, abandoned industrial sites. This is what the poem ‘Re-Wilding’ in The Last Almanac is all about, which I wrote on one of these adventures into the margins between nature and urban experience, noting the way they merge and meld together, how nature reclaims the spaces we carve out of it, and how this sense of separation is really an illusion, we are part of it and its within us. As you certainly show in your photography work.

You are, without a doubt, the most prolific writer I know. We’ve known one another for a long time (almost 20 years!), but there’s so much you’ve done that I didn’t even know about until I dug deeper. One of the thoughts that came to mind was that you must have burnt out at some point. Has it ever happened and if it did, how did you recover and move forward again?

I do get blocked from time to time, usually when I have completed a big ambitious writing project and then I think, shit, what now? But I, like I said earlier, I’ve learned to trust the process and give myself the space to move on from ‘the thing’ (whether it be Leasungspell, Civil Insolencies, The Seer Sung Husband for instance, which were all pretty consuming to create) so I start to see outside of its filter or lens. Its only when I can do that that fresh ideas start to bubble up.

One of my all-time favourite poems by you is Wolfling which you recorded with the collaborative collective Project Lono. Whenever I initially introduce people to your work, this is the poem I always go to first. I’ve been aching to know about your process for creating it and putting it to music.

Thanks, that’s very nice to know and again a lovely complement. Wolfing is another poem that is inspired by Peter and the Wolf, but this time it is responding to Angela Carter’s brilliant and disturbing version of the story.

I wanted to give a voice to the wolf-girl whose perspective the reader of the story doesn’t get access to, with the understanding that she has limited language and quite an alien sense of self. Because, over the years I have worked with many people who have limited vocabularies or language difficulties, in prisons, mental health institutions, in old folks residential homes with people suffering from dementia or Alzheimer’s, as well as others whose voices are just not heard or recognised, and perhaps the fact that my Dad has a stammer and struggles to articulate himself, I could see in the wolf-girl a really strong metaphor for all these struggling, marginalised and ignored voices that are full of fear, anxiety, confusion, frustration and anger. Which, I think comes through in the poem, especially in the Project Lono audio recording with the eerie discordant music behind it.

Can you recommend a poem by another poet that everyone should read?

Buffalo Bills by e.e. cummings, because it is weird and wonderful and playful and experimental and does not fit into most people’s pre-conceived notions of what poetry is.

Are you able to say anything about what you’re currently working on?

The sequel to Leasungspell is due for release from Smokestack Books this coming Autumn, It’s called Eftwyrd, so I’m working on the final proofread and edit of that manuscript. Over the last 3 years I’ve also been researching and writing about The Spanish Civil War and the Internationale Brigaders who went to fight Francoism, some from Teesside. I have 31 poems complete and there may be one or two more still to add, but the manuscript has been accepted by Drunk Muse Press in Scotland for publication in 2024. I’ve also been working on a novel called The Gallowglass Lalais, which is set in County Sligo in Ireland, and which I have the first full draft of now but need to go back and read carefully to see how to shape the next draft of it.

What’s the best advice you’ve been given about writing poetry?

I think it was Andy Croft that once said to me, “It’s a long road, and its your road, no one else’s.”

If you could give one piece of advice about writing poetry, what would it be?

That the writing you do at any one point isn’t necessarily the writing that you publish, but that doesn’t make it worthless. Quite the contrary, writing is an ongoing process of discovery. Often the writing you are engaged in is a vehicle to develop skills, understanding and insights, part of the creative process. So, write and read and write and read, and in the process (which is a long process) find out what only you can say.

Thank you.

You will be missed.

I wish you well in your future endeavours.

I hope we hear from you again.

Manja-Freyja.

My original response didn’t show up, so I wrote an edited, concise version. Now both are here. Always had issues with posting when it comes to WordPress.

WordPress is forever messing me about too! I feel you!

You will be missed, but I understand that things must happen and move on.

What a fantastic interview, you have much skill in the art of the interview.

Thank you for all your effort and all your work, you have helped change the course of my life through your music and your words; wonderful, wyrd words, that have inspired and given me much to think about.

All the best for the future. I wish you well, I hope we get to enjoy your words, perspectives, and thoughts again one day.

Manja-Freyja.

I am sorry it’s taken a while to reply here. Last week was horribly difficult. But I’m feeling rejuvenated after a beautiful weekend and want to express how massively grateful I am for you writing to me. ❤ It's comments such as this which give me strength to move forward with what I do. I'll be launching a new blog to replace WW&E and I really hope to see you there when it's live. (I'll be sure to post a link when it is. 🙂 Sending love and a blizzard of blessings to you my friend. x

Hi Katie,

I’ve been meaning to write this for a little while now and it never seemed like the right moment, but as this is to be the last post I suppose now’s my chance. I discovered your wonderful blog purely by chance last year (when combing the internet for dark art, no less) and couldn’t believe it when I found Wyrd Words And Effigies. Everything on here fascinated me – as a part-Swede, everything about the North, folklore and forests has mesmerised me from a young age, so I was overjoyed to find someone who shared my passion and had such a fascinating insight into life in the North. In addition to this, I have discovered so many great bands, being a black metal fan myself, as well as the witchy wonderfulness that is Cave Mouth. I must also mention how much I love your poetry and your incredible photography, you are such a talented and creative artist and writer. I suppose what I’m trying to say is, this blog has meant so much to me – it is as if you took all the things I love, and the feeling that goes along with them that I can never quite put into words (I’m sorry, this doesn’t seem to make as much sense as it did in my head) and put it all into this beautiful blog. Whilst you may no longer be writing on here, I hope you continue to write and create, and keep making the world a better and wyrder place. Stay strong, and I wish you the best of luck with all your future endeavours.

From Ryan 🙂

Ryan, I can’t even begin to tell you how much this comment means to me. Thank you, a thousand times over, for taking the time to share about what Wyrd Words & Effigies has meant for you. It’s so encouraging and makes me feel ever more motivated to launch my new blog. It’ll be called A Wyrd Of Her Own and I’ll be posting a link as soon as it’s live. Deciding to move on from WW&E was an extremely difficult but necessary decision which I’ll maybe one day write about. There has been so much self-doubt with all of my creative endeavours this year. I was even considering giving up with photography. But this thoughtful and beautiful comment has helped me to re-consider that. I really hope you’ll join me on my journey with my new blog. It would be an honour to have you come along for the ride. It may also be of interest to know, as someone else with a soul connection to the north, that I’ll also be re-launching my blog The Girl With The Cold Hands under a new name. I’ll post the link here too when it’s live. 🙂 With blessings of a wyrd kind, Katie. x